How to speak French like a Quebecker – Le québécois en 10 leçons

As you all know, I'm a huge fan of Quebec and especially of its French dialect (here's a video of me in French, interviewing a Quebec girl about the differences) and the wonderful people there.

Because I genuinely tried to speak like them while living in Montréal, rather than rigidly sticking to the French I had learned in Paris, I was warmly welcomed and had one of the best summers of my life! La belle province is definitely among my top five most favourite places on earth.

So this is why I'm happy to have a guest post today from a Quebecker, who has just published what looks to be the go-to-guide for anyone who wants to truly finally get their teeth into this wonderful dialect.

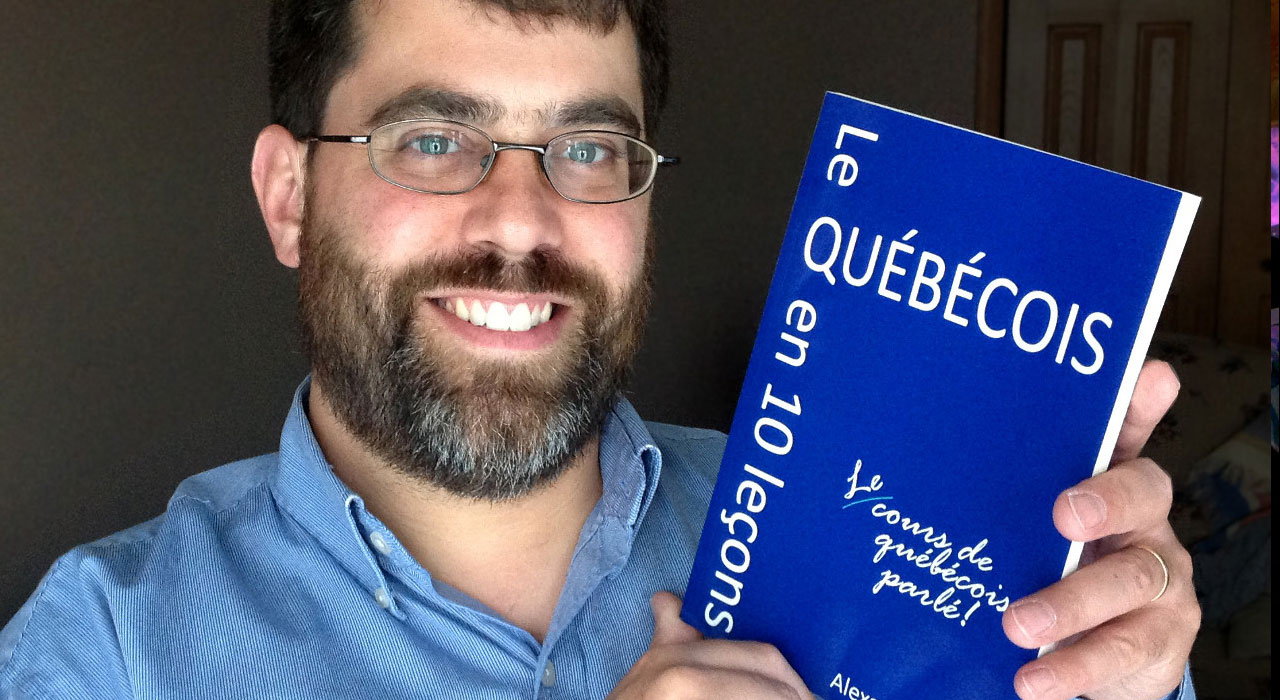

Alexandre Coutu (aka arekkusu or alexandrec on language forums) is a polyglot, translator, language coach, course designer and occasional interpreter. He just published a course on spoken Québec French called Le québécois en 10 leçons. Today he'll share some of the most prominent features of the dialect, and we've included audio samples so you can get a true taste for the how it truly sounds, as spoken by Quebecers!

Over to you Alexandre!

Why is French different in Quebec?

For most of us, the first encounter with a language happens in a textbook. This cold and clinical introduction sometimes leads people to believe that languages are set in stone, when in fact, it's quite the opposite: just like glaciers that are made of ice, yet fluctuate and change shape constantly, languages are liquid and continuously evolve.

One long term effect of that evolution is that languages that are spoken over large territories or in distant countries tend to evolve into different varieties that can sometimes cause the speakers — and the learners — to have problems understanding each other.

The case of French in Québec provides us with an interesting example. Over 400 years ago, when the first French settlers came to what they called “La Nouvelle-France”, most of these settlers came from regions North-West of Paris, such as Picardy, Normandy and Burgundy. The French spoken in these regions was considered to be the purest, and most resembled the King's French.

However, political changes in France caused Paris' dialect to become the country's prestige language variety; it's that dialect that eventually formed the basis of today's standard French. Meanwhile, the French spoken in what was later to become Québec continued to slowly evolve in its own direction.

The close ties that France and Québec have shared to this day have allowed the two linguistic communities to continue to understand each other, particularly in writing and in their respective standard forms, but there is no denying that a large number of differences in the informal language sometimes make mutual comprehension a struggle.

There are people who have the rather elitist vision that we should all speak the way we write and who wish Québécois didn’t exist. Unfortunately, many French language teachers hold similar views, and as a result, students are often left unable to understand “the man on the street”, even after years of study. This presents a particular challenge for students. As unbelievable as it sounds, many French classes in Canada use material geared towards France rather than Québec. So much for national unity.

A lot of beginning students of French are curious to know just how different Québec French is from France French. Some have likened the degree of difference to that of British vs. American English. This comparison could be considered valid if we only took the written standard language into account, but it is too weak an analogy when it comes to the spoken language.

Visitors with a good level of standard French will no doubt be understood in Québec, but without any knowledge of Québécois French, they will continue to be viewed as outsiders.

Most Québécois will try to use standard French with you, but it may feel a bit awkward and tiring for them. However, the Québécois will quickly warm up to anyone who shows an interest in their language. The origin of the visitor is irrelevant, it's the interest the person has in the Québec culture and language that will really open doors.

This is a point many English Canadians or other visitors often fail to understand. If you can use a bit of their language, they will immediately feel at ease, relieved that they can let their guard down, speak naturally and be genuine, and many will take you under their wing and try to help you learn.

Example dialogue, using real Quebec French

To give you a general idea of the kinds of things you hear in Québec, let's imagine that you are visiting Québec City. You are on the streets of le Vieux-Québec, looking lost. A stranger stops his car and asks:

J'peux-tu t'aider, mon gars?

This -tu may sound like the pronoun “you” but it's actually a question particle, similar to the Mandarin ma, the Esperanto ĉu or the Japanese ka, except that it follows a subject-verb group. Note that mec is never used in Québec: we only use gars.

You explain that you have to meet a friend at the train station and the man tells you:

Embarque, m'as t'amener!

Presumably because canoes used to play an important role on the banks of the St-Lawrence River, we use embarquer and débarquer to mean to get on or off any vehicle. In standard French, it's only used in reference to boats. M'as is a contraction of je m'en vais and indicates near future.

On the way there, the car’s air conditioner is blasting, and the driver tells you:

Pis, t’aimes-tu mon char? Si t’as frette, dis-moé-lé, gêne-toé pas!

In this sentence, pis is the equivalent of so, or alors. It can also replace et.

In Québec, auto is much more common than voiture, and informally, people say char. Frette means froid. As you can see, the order of words in the imperative form is different (dis-moi-le instead of dis-le-moi), moi and toi are often pronounced moé and toé, and the object pronoun -le can be pronounced -lé.

Since Québécois doesn’t use ne, the pronoun doesn’t move before the verb in gêne-toé pas.

After telling you what sounded like the history of the city (and the world), he drops you off at the station, and your friend's obviously been waiting for a while. She says:

T'as-tu eu d'la misère à trouver ‘a place? Ch't'icitte depuis une demi-heure!

Avoir de la misère means to have a hard time. Instead of saying the article la, your friend just said ‘a because la and les become ‘a and ‘es after a vowel. Ch't' means je suis (t is added before a vowel). Icitte means, as you probably guessed, ici. Many words ending in -i/-it become -itte (nuitte, litte, icitte).

Embarrassed, you apologize and explain that you got lost. Your stomach is growling, so you ask your friend:

Tu veux sortir déjeuner?

Your friend gives you a weird look… It's 1:30 pm already and you want to have breakfast?! In Québec, the meals are, in order: déjeuner, dîner, souper. She suggests:

M'as t'faire goûter à'a meilleure poutine au monde, c'est s'a rue St-Jean!

You've heard of poutine before but you never tried this fast food meal made of fries (patates frites), squeaky-fresh Cheddar cheese (fromage en grains) and beef gravy, so you are excited to give it a try! Some French prepositions undergo contraction (du, des, au, aux); Québécois has more contractions: here, à la becomes à'a (sounds like a long vowel). Sur is hardly recognizable:

sur le su'l

sur la s'a

sur les s'es

You get to the restaurant and your friend says:

Enfin! J't'après mourir de faim!

You figure she wouldn't be saying that AFTER she died, so you ask her to repeat. Turns out après means en train de — she's dying of hunger. Better order quick! The waitress comes; you manage to make yourself understood and you order a poutine. She adds:

Tu veux-tu une liqueur a'ec ça?

You don't mind hard liquor, but not usually this early. You figure this must be a local tradition, so you ask if they have Grand Marnier. Your friend bursts out laughing and explains that liqueur stands for soft drinks. The waitress looks at your friend and enquires:

C'tu ton chum?

She laughs again and says an unequivocal no. C'tu is a contraction of c'est-tu (remember the -tu question particle?) and chum means boyfriend (or buddy in some contexts). Looks like you've been friend-zoned. The waitress quips:

C'est d'valeur, y a l'air fin.

You can't see what value your hunger could have (did she say faim?), but she actually said it's too bad (c'est d'valeur) and she thinks you look nice (fin). Subject pronouns il and ils are always y in Québécois (it’s more systematic than in France). Elle is a.

You start to feel a bit more confident, so you figure you can try out some Québécois to ask for the bill. You know you can ask a question with -tu, and you also know that you have to use on instead of nous, so you say:

On peut-tu avoir l’addition?

The waitress laughs again. Oh well, you tried.

L’addition? Si j’te donne la facture, ça va-tu faire pareil?

Surprise! We don’t say addition, but facture. Bah, the waitress will think you’re even cuter for it. The rest of your question was perfect Québécois, after all! When she asks ça va-tu faire pareil?, she is asking if the alternative is good enough, something like Is that gonna be alright?

You make plans for the rest of the day with your friend when the bill finally comes. Oh, another surprise – there is a phone number on the bill! Now that’s going to come in handy…

As you can see, Québec French can be quite confusing without the proper explanations, but giving it a try is always worthwhile!

Le québécois en 10 leçons

Unfortunately, proper materials are hard to find: some websites present words and expressions in the form of a glossary, but only a few actually present explanations (I recommend www.offqc.com).

An overview of the printed material available on Québécois reveals a shocking reality: there is no course on spoken Québécois! There are dictionaries, glossaries and tourist guides, but nothing that is structured to teach the language as it's really spoken.

For more than 15 years, I've thought about writing such a book and finally, the project came to fruition in September 2012 as I self-published Le québécois en 10 leçons. You can sample the first lesson in which Simon visits the Québec Space Station to study whether beer can be made in space.

The course is divided into 10 lessons that present dialogues, grammar, vocabulary and exercises, all of which can be heard on free, downloadable recordings. It covers all of the most important grammar and vocabulary used in spoken Québec French.

Social