Spanish Irregular Verbs: The Ultimate Guide [with Charts]

Are Spanish irregular verbs giving you a headache?

Verbs are the biggest and most complicated topic in Spanish grammar. If you want to master them (especially if you want to master Spanish irregular verbs), you've got a lot to learn. But don't let that put you off.

In this article, we will look specifically at irregular verbs in Spanish. Here’s what we’ll cover:

Table of contents

Don’t be put off if you’re a complete beginner: I won't assume much if any existing knowledge of Spanish grammar.

Ready? Vamos! (“Let’s go!”)

Before we get into the article, if you are interested in learning Spanish yourself, you should check out my absolute favourite resource for learning Spanish, SpanishPod101.

Every time I refresh my Spanish, this has been by far my favourite resource, since it’s a podcast style learning resource that covers many aspects of the language much better than traditional courses do.

It also tackles the issue of listening comprehension better than literally anything else out there, since its catalogue of lessons eases you in with simple lessons at first that get progressively harder, and you can listen to them for a huge range of topics better suited to your hobbies and interests.

They have a free option for anyone who wants to test them out, based on just their limited recent episodes, but exclusively for Fi3M readers, you can get 20% off if you sign-up for any of their subscriptions, which allow you to access their full catalog of many hundreds of lessons, using the code FLUENT3.

I highly recommend this to all Spanish learners!!

What Are Irregular Verbs in Spanish?

To understand the difference between regular and irregular verbs, it helps to take a closer look at how verbs work in English. They usually follow a pretty simple pattern. I'll illustrate it with the verb “to walk”.

To use “to walk” in the present tense, you simply stick a pronoun in front of it: “I walk” or “they walk”. The one exception is the third-person singular form (he/she/it), which has an “s” on the end: “he/she/it walks“.

So far, so simple. Other tenses are just as easy: for the present continuous tense, you stick an “-ing” on the end of the verb and combine it with the present tense of the verb “to be”, as in “he is walking”. Or you can put an “-ed” on the end of the verb to make it past tense: “I walked”. These aren't the only tenses, of course, but the point is that the different forms of the verb “to walk” are made using some simple, consistent patterns that can be applied to many other verbs:

- walk, walks, walked, walking

- help, helps, helped, helping

- play, plays, played, playing

- climb, climbs, climbed, climbing

And so on.

Most English verbs follow this simple pattern; as such, they're known as regular verbs.

But then, there are verbs like “to speak”.

This word doesn't follow the pattern above; its past-tense version is not “speaked” but “spoke”. Similarly, “to buy” becomes “bought”, not “buyed”, and “to throw” becomes “threw”, not “throwed”. These are just a few of the many, many English verbs that don't play by the normal rules. These are the irregular verbs.

Spanish is similar. There are some basic patterns that most verbs – the regular verbs – follow, but there are also many irregular exceptions. If you want to communicate effectively in Spanish, you need to learn which verbs are irregular, and what their irregularities are.

But before we get deeper into the verbs that break the rules, let's review those rules.

A Quick Recap of Spanish Regular Verbs

Remember that Spanish verbs (regular or irregular) can be divided into three categories, based on the ending of their infinitive form:

- “-ar” verbs, such as hablar (to speak), cantar (to sing), and bailar (to dance)

- “-er” verbs, such as deber (to owe), correr (to run), and comprender (to understand)

- “-ir” verbs, such as vivir (to live), existir (to exist), and ocurrir (“to happen”)

The regular present tense forms in each case are:

| hablar | deber | vivir | |

|---|---|---|---|

| yo (I) | hablo | debo | vivo |

| tú (you, singular informal) | hablas | debes | vives |

| él/ella/usted (he/she/you, singular formal) | habla | debe | vive |

| nosotros (we | hablamos | debemos | vivimos |

| vosotros/vosotras (you, plural informal) | habláis | debéis | vivís |

| ellos/ellas/ustedes (they/they/you, plural formal) | hablan | deben | viven |

(Remember that the vosotros form is only used in Spain; in Latin America, use ustedes.)

Hopefully you've spotted some of the patterns. For example, the first-person singular forms all end with -o, and the second-person singular forms all end with -s.

You'll spot similar patterns when you learn the rest of the tenses. For example, in the first-person plural (the “we” form of the verb), Spanish verbs always end in “-mos” no matter what the tense:

- corremos – we run

- corrimos – we ran

- correremos – we will run

- corríamos – we were running

I won't go into depth here about all the different patterns and regularities you can find in Spanish verbs. Just remember this when you hear that a single Spanish verb can have almost 100 different forms. It's not as scary as it sounds: learn to spot the patterns, and it'll drastically reduce the amount of memorisation that you need to do.

While irregular verbs are less regular (duh), you tend to see the same sorts of patterns. No matter how weird an irregular verb is, you can still expect that the first-person plural form will end in -mos. Or, with very few exceptions, the first-person singular form will end in -o.

Bear this in mind as we explore the wild and wonderful world of Spanish irregular verbs. Always be on the lookout for the shortcuts that will make everything easier to learn.

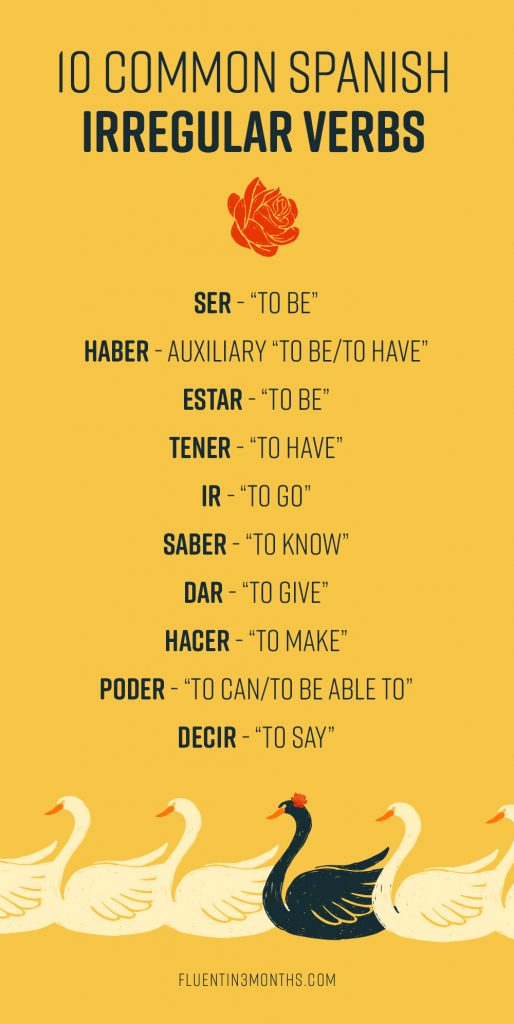

The 10 Most Common Spanish Irregular Verbs

Unfortunately, while most of Spanish verbs are regular, irregular verbs tend to also be the common verbs that get used the most often.

Here’s a list of 10 of the most common Spanish irregular verbs:

- ser – “to be”

- haber – auxiliary “to be/to have”

- estar – “to be”

- tener – “to have”

- ir – “to go”

- saber – “to know”

- dar – “to give”

- hacer – “to make”

- poder – “to can/to be able to”

- decir – “to say”

This makes sense when you think about it: the more often a word is said, the more chances it’s had to change and evolve over the centuries.

But let's think about English irregular verbs again for a second. There are many of them – but sometimes you find groups of words which all follow the same pattern, like “blow, blew”, “throw, threw”, and “know, knew”.

If you remember that these words all go together, you can learn them as a single unit.

Thankfully, Spanish irregular verbs can often be grouped like this too. So let's look at the most important groups to learn.

The Spanish Irregular Verbs by Category: Stem-Changing Verbs

The simplest irregular verbs in Spanish are the so-called stem-changing verbs. They're easy to learn.

The “stem” of a verb is the part you get when you remove infinitive suffix (that is, the -ar, -er, or -ir) from the infinitive form. So the stems of hablar, deber, and vivir are habl-, deb-, and viv-.

When dealing with regular verbs, you never change the stem. All you do is remove the infinitive suffix and add an ending like -o or -as.

Many verbs, however, are more complicated. I’ll show you with an example.

Here are the present-tense endings of cerrar (“to close”). Pay close attention to the stem:

- cierro – I close

- cierras – you (s.) close

- cierra – he/she closes

- cerramos – we close

- cerráis – you (pl.) close

- cierran – they close

Do you see what's going on?

In the first, second, third, and sixth forms, the vowel in the stem changes from e to ie. Other than that, everything is as normal – the endings are what you would expect if the verb was regular.

It might seem confusing that the stem only changes in four of the six verb forms. To understand why this is the case, focus on the -amos/-áis forms. The stem is unstressed: in both of these cases, the stress goes on the second syllable.

The vowel in the stem of a stem-changing verb only changes in those conjugations where that vowel is stressed. In practice, you only need to know that these are the yo, tú, él/ella and ellos/ellas forms.

But it's better if you understand why this is the case. It's as if you're “stressing” the vowel so hard that it breaks apart into two pieces.

To understand why the stem's vowel is stressed in some verb forms and unstressed in others, see this detailed explanation of accents and word stress in Spanish.

Types of Stem-Changing Verbs in Spanish

There are three main types of stem-changing verbs in Spanish.

There are also a few weird ones which don't fit into those three main categories, but we’ll talk about them later in the post. I'll start with the categories.

First of all, you have verbs which change an e to an ie. We've already seen cerrar above, which follows this pattern. Some of the most important similar verbs are:

- acertar – to guess

- advertir – to advise, warn

- atender – to attend to

- atravesar – to cross

- calentar – to warm/heat (up)

- cerrar – to close

- comenzar – to begin

- confesar – to confess

- consentir – to consent

- convertir – to convert

- defender – to defend

- descender – to descend

- despertarse – to wake up

- divertirse – to have fun, enjoy oneself

- empezar – to begin, start

- encender – to light

- encerrar – to enclose, encircle

- entender – to understand

- fregar – to scrub

- gobernar – to govern

- helar – to freeze

- hervir – to boil

- mentir – to lie

- negar – to deny

- nevar – to snow

- pensar – to think

- perder – to lose

- preferir – to prefer

- recomendar – to recommend

- remendar – to mend

- sentar(se) – to sit down

- sentir – to feel

- sugerir – to suggest

- tropezar – to stumble, trip

Secondly, verbs which change an o to a ue. For example, here's colgar (“to hang”) in the present tense:

- cuelgo – I hang

- cuelgas – you (s.) hang

- cuelga – he/she/it hangs

- colgamos – we hang

- colgáis – you (pl.) hang

- cuelgan – they hang

Here are some more examples from this category:

- absolver – to absolve

- acordarse (de) – to agree on

- almorzar – to eat lunch

- aprobar – to approve

- cocer – to bake

- colgar – to hang

- conmover – to move (emotionally)

- contar – to count, to tell

- costar – to cost

- demoler – to demolish

- demostrar – to prove, demonstrate

- devolver – to return (an object)

- disolver – to dissolve

- doler – to hurt

- dormir – to sleep

- encontrar – to find

- envolver – to wrap

- llover – to rain

- moler – to grind

- morder – to bite

- morir – to die

- mostrar – to show

- mover – to move (an object)

- poder – to be able to

- probar – to prove, sample, test

- promover – to promote

- recordar – to remember

- remover – to remove

- resolver – to resolve

- retorcer – to twist

- revolver – to mix, shake

- rogar – to beg, pray

- soler – to be accustomed to, to usually be/do

- sonar – to sound, ring

- soñar – to dream

- tener – to have

- torcer – to twist

- tostar – to toast

- tronar – to thunder

- volar – to fly

- volver – to return (from somewhere)

The third common category of stem-changing verb is that of verbs that change an e to an i. For example, corregir (“to correct”):

- corrijo – I correct

- corriges – you (s.) correct

- corrige – he/she corrects

- corregimos – we correct

- corregís – you (pl.) correct

- corrigen – they correct

Here's the list you should learn:

- colegir – to deduce

- competir – to compete

- conseguir – to get, obtain

- corregir – to correct

- decir – to say

- despedir – to dismiss, fire, say goodbye to

- elegir – to elect

- freír – to fry

- gemir – to groan, moan

- impedir – to impede

- medir – to measure

- pedir – to ask for, order

- perseguir – to follow, pursue, persecute

- repetir – to repeat

- reír(se) – to laugh

- seguir – to follow, continue

- servir – to serve

- sonreír(se) – to smile

- vestir(se) – to get dressed

And finally, here are the weird stem-changing verbs that don't quite fit into the above categories.

First, the verb oler (“to smell” – either to smell an object, such as a flower, or to emit an odour). This might look like a o to ue stem-changing verb, but when the stem changes, you must add an “h” to the beginning:

- huelo – I smell

- hueles – you smell

- huele – he/she/it smells

- olemos – we smell

- oléis – you (pl.) smell

- huelen – they smell

(Remember that an “h” in Spanish is always silent, so this extra letter doesn't have any effect on the pronunciation.)

Second, the verb jugar. It’s the only example of a verb whose stem changes from a u to a ue:

- juego – I play

- juegas – you (s.( play

- juega – he/she/it plays

- jugamos – we play

- jugáis – you (pl.) play

- juegan – they play

Third, two verbs exist that change an “i” to an “ie”. They are adquirir (to acquire) and inquirir (to inquire). So in the first-person singular they're adquiero and inquiero, respectively. Can you figure out the other five present-tense forms of adquirir and inquirir? Hopefully by now it should be easy.

Spanish Verbs With an Irregular “yo” Form

I told you earlier that decir (“to say”) is an e- to -i stem-changing verb. But it’s not only that. Decir is also one of a small number of verbs which has a non-standard yo form.

Remember that yo means “I”. “I say” is (yo) digo, which isn't what you'd expect if you followed the rules above.

To be clear, here are all six present-tense forms of decir:

- digo – I say

- dices – you (s.) say

- dice – he/she says

- decimos – we say

- decís – you (pl.) say

- dicen – they say

As you can see, the first form uses the weird -go suffix. The rest of the forms proceed as normal, subject to the stem changes that I already explained.

Several other common Spanish verbs follow this pattern in the present tense. The first-person singular form is irregular; all other forms are either regular or, as in the case of decir, have a stem change.

Here's what you need to learn. For each verb, I'll give the infinitive, the first-person singular (which is irregular), and the second-person singular (so you can see the stem change, or lack of it).

Irregular “yo” form with no stem change

- conocer – “to know” – yo conozco, tú conoces

- dar – “to give” – yo doy, tú das

- hacer – “to do, make” – yo hago, tú haces

- poner – “to put” – yo pongo, tú pones

- salir – “to exit” – yo salgo, tú sales

- traer – “to bring” – yo traigo, tú traes

- ver – “to see” – yo veo, tú ves

- oír – “to hear” – yo oigo, tú oyes

- saber – “to know” – yo sé, tú sabes

- ir – “to go” – yo voy, tú vas

- estar – “to be” – yo estoy, tú estás

- caber – “to fit” – yo quepo, tú cabes

- lucir – “to wear” – yo luzco, tú luces

- valer – “to be worth” – yo valgo, tú vales

Irregular “yo” form with a stem change

- decir – “to say” – yo digo, tú dices

- tener – “to have” – yo tengo, tú tienes

- venir – “to come” – yo vengo, tú vienes

Ser

It's time to look at the biggest and baddest of all Spanish irregular verbs: ser, which means “to be”.

Like its English counterpart, ser is highly irregular – and not just in the first-person singular. Here are the six present-tense forms of ser:

- soy – I am

- eres – you (s.) are

- es – he/she/it is

- somos – we are

- sóis – you (pl.) are

- son – they are

I recommend you learn these conjugations by memory as soon as possible. It's probably the most important irregular verb in Spanish, and it will show up in most of the sentences you’ll see, hear, read, or speak.

Haber

Another highly irregular (and important) verb is haber. The dictionary might tell you that haber means “to have”, but this doesn't paint the full picture.

To say “I have a dog” in Spanish, you'd say “tengo un perro”. Tengo, as we saw above, is the irregular first-person singular form of tener, and tener is the normal way to say “have” in this sense in Spanish.

So where does haber come in?

Think of an English sentence like “I have eaten “. The word “have” is doing something different here. It doesn't mean ownership or possession, which is what tener is for.

Instead it's a grammatical device that changes the tense of the word. In this case, it tells you that the action took place in the past.

This is the primary function of haber in Spanish: it's used in compound tenses, like the “have” in “I have eaten”.

Here's how it's conjugated (and I'll stick with “eaten”, comido, as my example):

- he comido – I have eaten

- has comido – you (s.) have eaten

- ha comido – he/she/it has eaten

- hemos comido – we have eaten

- habéis comido – you (pl.) have eaten

- han comido – they have eaten

The End of the Beginning

This might seem like a lot, but you don’t need to learn everything now.

For one thing, if you still haven’t got a solid grasp of regular verb endings, you should work on that before worrying too much about irregular endings. If you need help with these, take a look at Benny’s post on the three main Spanish tenses.

When you feel ready, come back to these irregular endings, and, as always, don’t be afraid to make mistakes! If you forget which verbs are irregular, and say something like yo sabo instead of yo sé, people will still understand what you mean.

In fact, mistakes like “yo sabo” are common among children who are learning Spanish as their first language – which just goes to show, it doesn’t always come naturally even to native speakers!

Social