Reflections on learning a language remotely: How polyglot Olly Richards is updating his previous in-country learning method

On Friday, I can get back to updating you all on how my Japanese is going. For now, I thought I'd share the thoughts of another travelling Polyglot, Olly Richards, who writes about strategies for language learning at iwillteachyoualanguage.com

Olly, from the UK, is among the many people who have joined in on the +1 challenge, and has taken on Cantonese, even though he is currently in Qatar! This distance learning is something I know many of you can relate to (I certainly can nowadays!) and I found his reflections based on having already learned languages in the countries or communities quite interesting, and something I could learn from myself.

His thoughts reflect mine that you really can learn any language anywhere and I liked reading about how he adapted his success in-country to his current project.

Connect with Olly on Twitter, Facebook and Google+. To follow his progress in Cantonese be sure to check out his YouTube channel.

It was all going smoothly until language number seven came along. This time was different. The “method” that I’d applied so well up until this point was suddenly no use to me. I felt like a fraud.

The language: Cantonese (the Chinese dialect of Hong Kong). The place: Doha, Qatar.

And that was the problem.

You see, by all accounts I’ve been a pretty successful language learner, but the truth is that every time I’ve learnt a language I’ve either been living in the country itself (twice) or else had a community of people around me who spoke the language I was learning (four times).

With those surroundings, enough motivation and a bit of time, it’s not all that hard to pick up a language. But learning Cantonese in Qatar was different. As a social person who relies on the people around him not only to practice but to provide the motivation to learn, this mission felt like I was a very long way up a certain creek with no paddle in sight.

In Doha I had no Cantonese friends to meet, no-one to practise with and one mother of an uphill struggle ahead of me. I felt like an F1 driver who’d just traded his Ferrari for a Skoda.

And yet I was still determined to learn. Funny how that happens 🙂

What followed was an intense couple of months of haphazard study, experimentation and reflection. I hit some brick walls, made progress, followed by no progress, had a few breakthroughs and almost gave up!

This rollercoaster ride wasn't like it used to be, and it wasn’t very pleasant.

Being on my own, I was forced to analyse the problems I was having and think long and hard about how to replicate the conditions that had led to success in the past. I deconstructed how I’d learnt each of my other languages, drilling down to exactly how I did it – what worked, what didn’t, what kept me going and what pissed me off (there was a lot in this last category!).

I came up with ways to replicate that success in ways that could be done in isolation and didn’t rely on society around me, and applied them to each problem I was having in Cantonese. I emerged on the other side with a rare feeling of clarity. Having deep-dived into my own learning process, I had a strong idea of where I was going and how to get there.

Language learning techniques that I’d used intuitively in the past had now been crystallised and laid out into clear steps.

This is the story of how I reinvented my method and synthesised ten years of experience into a coherent approach to learning a language remotely; a set of guiding principles and strategies that can be used by anyone studying on their own.

Let’s start with a case study of how I learnt French. We'll then compare that to my current Cantonese predicament and end with the lessons I’ve learnt about remote language learning.

Notes

You might notice that only some of this approach deals with language itself. The rest deals with time-management, psychology, self-reflection, etc. It is my strong belief that language learning does not require any particular skill, only the right conditions for learning to take place. That is what I’m aiming for here.

At the time of writing I still have a long way to go in Cantonese. However, after only three months of working no more than 1 hour per day, I’m considerably further on than at the same stage in any other language I’ve learnt.

As a reference, here's my 2-month progress update:

Case study: Paris, 2000. (True story!)

The 19 year-old Olly boards a Eurostar train in London Waterloo. Destination: Paris. He’s a bit lost. The break up with his girlfriend of 2 years has been tough and he needs a change of scene.

Being the stubborn type, he’s determined to make a success out of this sojourn to Paris, hence the one-way ticket in his pocket.

Olly’s French level is not good. Despite having studied at school, three years have passed and he has never spoken with an actual French person. That said, he can probably manage to order food in a restaurant and buy a train ticket.

The first three weeks in Paris are spent in an English friend’s studio flat. After getting kicked out, he finds a youth hostel in the quartier latin.

Things aren’t looking good.

Far from improving his French, he’s surrounded by foreigners and speaking English all day.

The hostel owner offers him a job at reception in another hostel in lovely Montmartre, working night shifts two nights a week. With nothing else to do, he takes it.

It begins!

His new boss hardly speaks English. During induction, Olly nods a lot and pretends he understands what the job involves. When there’s something that looks really important, he asks for clarification.

He starts work the next night. Although there are many foreign guests, there are also plenty of French, and Olly finds himself dealing with customers and answering the phone in French.

He’s way out of his depth, but sheer audacity sees him through. He’s learning a lot – the same words and phrases keep cropping up so he learns all the important stuff quite quickly. He learns how to understand what people are saying by focussing on key words and guessing the rest.

A French guy comes into the hostel and asks him if he’s interested in an English-French exchange, where they would help each other learn their respective languages. Olly loves the idea and they start meeting twice a week for very productive sessions.

He was quickly able to clarify all the language questions that had been on his mind for a while and have some language and pronunciation errors corrected.

One night Olly goes to a party organised by friends at the other hostel, where he’s still living. A girl takes a liking to him and they start seeing each other. She doesn’t appreciate his speaking French with an English accent and starts to aggressively correct his pronunciation. She’s very French.

And so it went. Work was tiring, but it was Olly’s only source of income, so he had to keep going. But it was also a lot of fun – the international guests were cool and it meant he didn’t have to speak French all the time.

Six months later it was time to go home. Olly went back to London one language richer and with a newfound passion for languages. The girl didn't fancy London, so she stayed waved goodbye.

Deconstructing the learning experience

Much of the time, I was having so much fun that the French almost taught itself. My subsequent languages were learnt in a similar fashion – led by circumstances.

I learnt that creating the right conditions is critical. Get this right and the job is a lot easier.

Returning now to my current project of learning Cantonese in Doha, there are seven key areas that I’ve struggled with:

- Accountability

- Emotional attachment

- Knowing yourself – building a routine

- Choosing what to learn and how

- Start speaking and get feedback

- Taking time off

- Perfecting your accent

Let’s compare my current struggles with my successes in Paris, and see where the gaps are.

1. Accountability

Paris: I’d left London to go to Paris and all my friends and family knew it. There was no way in hell I was going home without speaking good French .

The truth is, whether I was ultimately successful at learning Cantonese or not, there were no consequences for me.

If you want to quit smoking , the first advice given is: tell your friends about what you’re doing. This is accountability.

Learning a language in isolation is a long, hard slog, and you’re often just one bad-day-at-work away from throwing your copy of Pimsleur at the cat and calling it a day.

It’s vital to involve other people in the mix to make you think twice about quitting. As it happened, a golden opportunity came my way in the form of Brian Kwong’s add1challenge (now the Fluent in 3 Months Challenge). (This is an online group of people who support each other during a 3-month language challenge.)

Joining the add1challenge got me to a place where I had the following stakes: 1) Join an online group where everyone was learning a language (i.e. tell people about it); 2) commit to posting progress videos every month; 3) a live, unscripted conversation after 3 months of the challenge to be videoed and posted to YouTube.

For those of you who want to start now, you can also share your journey publicly on the Fluent in 3 months forums, where many people will interact and offer their support.

This kind of accountability now makes me think twice about taking time off and serves as an added kick in the backside to study when I’m not in the mood. For the ultimate in public accountability, I defer to Mr. Lewis himself!

The higher you aim, the harder it’ll be to let yourself fall!

2. Emotional currency

Paris: I was learning French in the French capital with a French girlfriend. Enough said!

How about Doha? Err, living in the desert surrounded by Arabs. And a cat. Hardly conducive to learning Cantonese.

After my first few weeks of studying, when the grind started to set in, I found myself thinking “Why am I doing this, again?” With nothing around to inspire me, how was I going to keep going?

I thought back to what I loved about Cantonese culture.

I thought of my love of Hong Kong cinema. From Bruce Lee to Andy Lau, I can’t get enough of it. I spent time stocking up on movies and also came across some fantastically cheesy yet addictive TV dramas (a vice that I picked up in Japan).

Watching dramas led to the discovery of some great Cantonese songs (often used as theme tunes to the dramas), and before I knew it I had a collection of cinema, TV and music that I was really excited about and couldn’t wait to get started on.

Voilà, the emotional attachment.

When times got tough with the studying later on, as they invariably do, you still couldn’t have dragged me away from Andy Lau and Beyond.

If you’re learning your girlfriend’s language, or living in the country itself, you have significant emotional stakes – your learning has an immediate impact on your life.

At those times when you can’t seem to make any progress, it’s your emotional attachment to a language that gives you the drive to carry on. Where accountability is the external motivator, emotional currency is the internal one.

Attack it from both sides and you’re in a much better position.

Learning at distance means you have to nurture the emotional connection with the language. But how to do this? Find something about the language or culture which fires you up. If you’ve made the decision to learn a language in the first place, it shouldn’t be too hard to pin this down. Start spending some money on Amazon and collecting things you like!

Proactively building your emotional attachment to the language provides continuity and doesn’t place all your eggs in one basket.

3. Know yourself – building a routine

Paris: My routine was imposed upon me by scheduled meetings with my language partner and having to use French at work. I didn’t have to make any particular effort to study. (How I miss that!)

Eighty percent of success is showing up. (Woody Allen)

At first, without any particular pressure, I began chipping away at books and CDs. I chopped and changed, and before long I started to find it difficult to sit down and study. I’d say to myself “What should I be doing now? Do I have to? Does it matter if I don’t?”

Without structure your mind will start to play tricks on you.

It’s impossible to understate the importance of effective routines if you intend to make rapid progress. Repetition, it is often said, is the mother of skill. The simple act of repeating something day after day will bring results.

I’d go so far as to say that it doesn’t matter how you study, or how fancy your techniques are, if you don’t do it regularly it’s a waste of time.

And so to avoid over-complicating the issue: you need to move heaven and earth to make a study routine that you can stick to.

To find a routine that worked for me I went through some difficult stages, but got there eventually, via the following rationale.

- Recognise how your brain works. You've decided to learn a language, and you're absolutely determined to do it. So, in a show of bravado, you want to give yourself a hardcore study schedule of 2-3 hours per day in order to become fluent as quickly as possible. You do this because you've got high standards and don't want to sell yourself short with a mere 1 hour a day. You do this because you're scared of failure, and this is called pride.

- Recognise the implications of sticking successfully to your routine. If you get it right, and keep it up, the benefits are immense: pride, increased motivation, better self-control, and… improved learning. “Showing up.”

- Recognise the consequences of not sticking to your routine. If, for whatever reason, your routine gets the better of you, the consequences can be serious: frustration, confusion, beating yourself up, corner cutting… and, ultimately, giving up.

- Getting your routine right is more important than what you're actually doing in it. Look again at points 2 and 3. One is massively empowering, the other devastating. It's clear what to aim for.

- It's easier to scale up than to scale down. If you start small, it's easy to scale up, and you'll feel good about it. If you start big, and it doesn't work, you'll find it hard to feel positive about cutting back (sounds like failure, right?).

- Not all time is equal. I know that certain times of day, or certain places, carry a high ‘distraction factor'. For example, I'm at high risk of distraction at around 5pm just after I've got home, because I'm tired and tempted by any number of things.

By contrast, I can do almost anything early in the morning when there's no-one around. By recognising the ‘distraction factors' over the course of your day, you can plan work for those times when you know you’ll be alert.

So, in short, when putting together your study routine, you have everything to lose and nothing to gain by aiming too high. Start modestly, and don't feel guilty about it. Get this right, and scale up.

Here's how I'd summarise my approach now:

Don't delay. Decide on a study routine that's 100% achievable (however small), write it down somewhere and get started. Start with as little as 15 minutes per day, if necessary, and schedule it for a specific time.

In reality, you'll probably enjoy the process so much that you will do more than your scheduled 15 minutes, so it becomes a way to trick your brain into getting started. After 3-4 weeks this will become a habit and you won't need to try so hard any more.

As you settle into your routine, only then should you begin to expand. Decide on the times that you'll study and what you'll do in each slot – make it achievable above all. Here's what I’m currently doing:

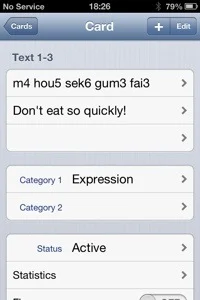

- on waking up: SRS flashcards

- driving to work: podcasts in Cantonese

- when I get home: 30 mins-1 hour focused study

- evening/down time: TV/movies in Cantonese

- before sleep: SRS flashcards

So, it’s anything from a total of 1 hour per day up to 3 hours if movies are involved. If I only do the minimum, that’s fine. The key is in the routine. Day in, day out.

The secret is to make your routine so clear that you do it without thinking (e.g. as soon as I get in the car, a podcast goes on), so it's vital to be clear and specific about your routines right from the start.

4. Choosing what to learn

Paris: Using French at work created a sink-or-swim situation. I needed certain words and phrases to survive, so whenever there was something I didn’t understand I learnt it quickly and without fuss.

It was clear to me, though, that if I was going to make progress and sustain it, I needed to create the same sense of urgency as on my first day of work in Paris – sink or swim.

How?

Well, I want to start speaking with native speakers as soon as possible. It’s what I enjoy, so I make it priority no.1.

So then, rather than ploughing mindlessly through my text book, I try to be more selective.

Text books present you with lots of options: language exercises, drills, writing tasks etc. I suggest largely ignoring them and focusing on the vocabulary.

Do this by choosing the most obviously useful words and phrases from the texts. Words that you are likely to want to use or be able to understand in conversation, putting them directly into an SRS app and then studying them consistently. Be sure to record vocabulary as words within phrases – do not learn single words on their own.

On top of this, I need certain words and phrases in order to speak, and my approach has been quite simple: figure out what words and phrases I need and go learn them!

So in addition to working through a self-study resource, I’ve developed an extensive list of words and phrases (I call it high-impact language) that I now know I am likely to want to use in conversation, and I can take this list with me for each new language that I may come to in the future.

5. Start speaking and get feedback

Paris: I had direct feedback from my language partner and from my girlfriend (a little bit too much of the latter!). Customers in the hostel also didn’t hesitate to let me know when they didn’t understand my French!

I’ve lived, or spent extended periods, in five foreign countries and the first few weeks in each were characterised by a lot of challenging conversations as I learnt to get by.

I find this kind of stress healthy and motivating. The act of communicating in another language, however poorly, I find exhilarating and it spurs me on.

To speak from day one, or not to? This is a debate that readers of fi3m will be well aware of, so I’ll just tell you where I stand.

After a few weeks, or after building up enough vocabulary to get across some basic meaning, I like to start having conversations in the new language.

So from my base in Doha, I started my speaking sessions with an online tutor, thereby replicating the healthy stress that I would have had by moving to Hong Kong and finding my way on the streets.

This was an easy decision to make – I knew that going very long without speaking would have blown my motivation right out of the water. If you’re going to struggle anyway, why not do it from the comfort of your own home? Some may even say it’s better that way.

Here’s the thing.

It ain’t all that easy to “just speak” with a tutor, as with a conversation partner. Why? Because they will invariably want to “teach” you.

Remember: the goal of your speaking sessions is not to be taught. (You can teach yourself.)

You want to replicate the struggle of communicating in the foreign language, using no English. Through that struggle you will develop the familiarity with the language to function in any situation.

Have a heart-to-heart with your tutor and lay down some ground rules:

- 1 hour pure speaking. It's enough to stretch you but not so long that you start tearing your hair out.

- No English. The main aim is to develop aptitude, competence and familiarity with the language. That won't happen if you use English to mediate the conversation. Will it be difficult sometimes? Will you sometimes be lost for words? Yes. But from that struggle emerges your ability to deal with unfamiliar situations and unknown language.

- Your tutor needs to do two things as conscientiously as possible. Firstly, to let you speak and not interrupt with corrections every 5 seconds. Explain that you don’t need “teaching”. Secondly, to make efforts to keep the conversation going and not put all the onus on you to speak. Basically, they are not there to teach, but to promote conversation and answer your questions when needed.

Prepare for speaking sessions by deciding topics you’ll be talking about, revising language related to those topics and preparing questions that you can ask.

This is time well spent as you support yourself into the speaking process with preparation and someone who’s willing (or being paid) to listen.

It builds confidence and gives you a framework within which you can make plenty of mistakes – something we should be actively seeking, according to Luca Lampariello.

6. Downtime

Paris: I didn’t speak French all the time. I had some non-French friends and the hostel I worked in was full of travellers. I would sometimes go for days on end not speaking all that much French. What I didn’t do was doggedly study everyday.

It was never a problem for me to keep going before. I was always propelled along by my friends and people around me.

This time – learning at distance and in isolation – this element has been the hardest to get right.

Thinking back to Paris, it’s clear that my learning took place in a context of fun and excitement, not dedicated studying.

The key to beating the motivation blues this time has been actively finding ways to relax and have fun with the language.

I’ve settled on two areas as being most important

Firstly, separate study time and downtime. Do your prescribed study time, then clock off and have fun. Take your study hat off and bask in the language – remember your list of movies/books/songs etc. from earlier? The stuff that gets you excited? Now’s the time to get them out, use them to have fun and relax.

During this time, put your dictionary away and just soak it all up.

As something of a workaholic, it’s been difficult for me to accept this. However, coming to accept that “study time in” does not equal “progress out” (80/20), has been one of the most important learning points for me.

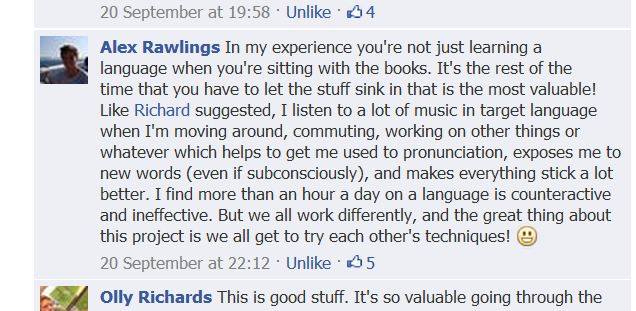

On this topic, I took particular inspiration from two places. Firstly, this interview with Anthony Lauder (watch from 28:00). Secondly, a piece of advice given to me by Alex Rawlings after I’d complained about not having enough hours in the day:

[Used with permission]

Secondly, know when to step back. I had a case of burnout recently, where I didn’t want to study and my motivation had dropped off a cliff. I ended up taking a week off, all the time beating myself up for doing so.

After a lazy week, I finally revisited my flashcards.

I was surprised to find that dozens of tricky cards that I'd been struggling to remember for some time were suddenly no problem at all – it was as if I'd known them for years.

This confirmed an important concept to me: the brain continues working while we rest.

We need to take time off from studying and give our brains space to breathe and process all the information we've been feeding it. It also supports Alex’s earlier argument of not doing more than 1 hour per day.

Feel like a break? Take a week off and enjoy it!

Your brain will thank you for it.

7. Perfecting your accent

Paris: Being endlessly told by my girlfriend that I “didn’t sound French enough”, followed by exhaustive corrections, quite quickly ironed out any creases in my pronunciation. I also got turned on to some great French bands, like IAM, and learnt quite a few songs – picking up some pretty serious verlan at the same time!

The big danger in learning from distance is not getting enough feedback on your language.

Learning Cantonese, for example, I was well aware that tones were going to be an issue, and the importance of getting them right. Other languages present other difficulties, but pronunciation is invariably something that it pays to get right from the start.

Pronunciation is a big deal and I like to get help on this from a native speaker right from the start.

So, I found a native speaker tutor online, but rather than using him for conversation practice, I focused instead on two things:

- Asking him to teach me natural ways of talking about myself and what I do. This, aside from being useful in itself, it’s a vehicle for…

- Working on my pronunciation. Using the words and phrases from 1., I had him correct my pronunciation in minute detail.

Don’t skimp on this – it's laying the foundation for everything to come. It’s particularly important if you’re learning a tonal language, but applies equally to any other.

Having worked on my tones with the tutor, I knew that I had to find ways to practise and apply them and learning songs was the obvious choice.

In the spirit of mixing things up and getting your head out of the textbook, music is an amazing asset.

We know that there is a strong connection between music and the emotions, making songs ideal for building that emotional engagement with the language you need to keep going while on your own.

There’s no doubting it’s a lot of work to learn a song, but you will find that you never forget the lyrics once you’ve learnt them, making it a great investment of your time!

There are many tangible benefits, the most considerable of which is pronunciation. Singers usually articulate their words very clearly, which helps to get your pronunciation spot on from the beginning.

Music is massively important for me – some years ago I went as far as forming a salsa band and writing a load of songs in Spanish! Here’s one recording of my band (I’m on piano and backing vocals!):

I'm not sure if I'll ever go so far as to write music in Cantonese, but who knows!

Conclusion

There are many reasons for learning a language and even more ways to actually do it. No one method is more valid than any other.

Having a number of previous language learning experiences to draw from, my Cantonese mission has forced me to be clear about what I do by finding ways to replicate what has worked for me in the past.

For anyone who wants to learn a language, the key lies in understanding how you work best and how you learn.

If you’re learning remotely, and this is your first language learning experience, it’s even more important that you take the time to look inside.

I hope the ideas in this post, whether they work for you or not, will inspire you to reflect on how you learn, and become the best language learner that you can. To help you put the ideas into action, I've put together a printable PDF checklist that you can download for free here.

Experiment, reflect, record, adapt, rethink and above all… have fun!

Social