French Accent Marks: The Ultimate Guide

What are French accent marks, and why do they matter? The words café and résumé are originally French, and in English we often write those words without the accents. In French, however, the accent marks are not optional.

Getting your accents right is the difference between being a pêcheur (fisherman) and a pécheur (sinner). Which one would you rather have on your résumé?

So let’s look at the different types of French accent marks and how they’re used. We’ll cover all the different types of accent marks, how they’re pronounced (if they’re pronounced at all), and the effect they have on a word’s grammar and/or meaning.

We’ll also look at plenty of examples of French words with accents which should help make things clear. Plus, I’ll teach you how to type them on a PC and Mac (with keyboard shortcuts!).

Table of contents

- French Accent Mark List: The 5 French Diacritics

- The Cedilla (La Cédille) Accent Mark in French

- The Acute (L’Accent Aigu) Accent Mark in French

- The Grave (L’Accent Grave) Accent Mark in French

- The Circumflex (L’Accent Circonflexe) Accent Mark in French

- The Trema (L’Accent Tréma) in French

- How to Type French Accents

- How to Type French Accents On a PC

- How to Type French Accents On a Mac

- French Accent Marks – Have Your Say

Before we get into the article, if you are interested in learning French yourself, you should check out my absolute favourite resource for learning French, FrenchPod101.

Every time I refresh my French, this has been by far my favourite resource, since it’s a podcast style learning resource that covers many aspects of the language much better than traditional courses do.

It also tackles the issue of listening comprehension better than literally anything else out there, since its catalogue of lessons eases you in with simple lessons at first that get progressively harder, and you can listen to them for a huge range of topics better suited to your hobbies and interests.

They have a free option for anyone who wants to test them out, based on just their limited recent episodes, but exclusively for Fi3M readers, you can get 20% off if you sign-up for any of their subscriptions, which allow you to access their full catalog of many hundreds of lessons, using the code FLUENT3.

I highly recommend this to all French learners!!

French Accent Mark List: The 5 French Diacritics

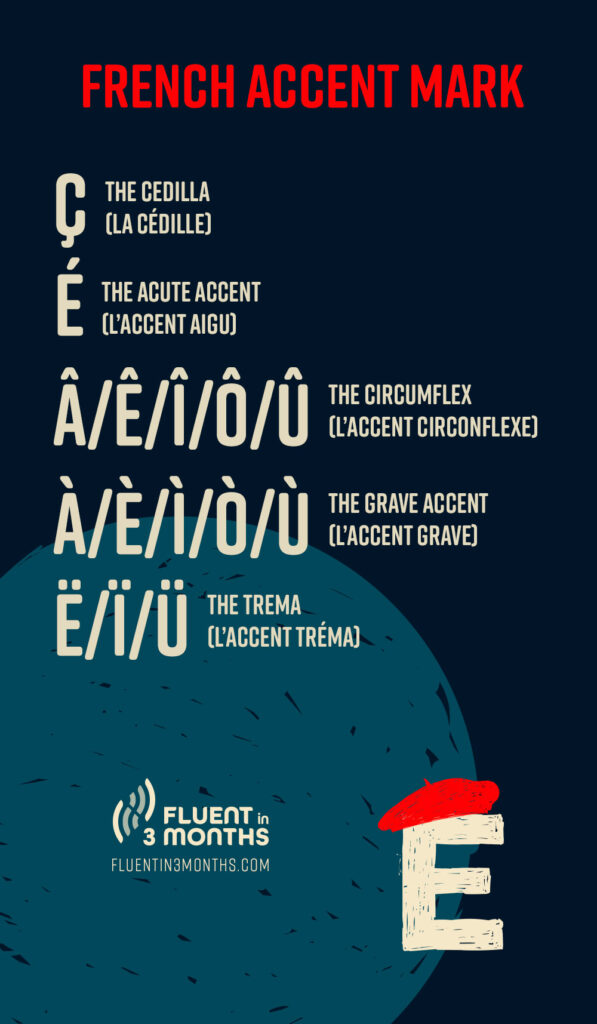

French accent marks are comprised of five different diacritics.

In no particular order, they are:

- ç – the cedilla (la cédille)

- é – the acute accent (l’accent aigu)

- â/ê/î/ô/û – the circumflex (l’accent circonflexe)

- à/è/ì/ò/ù – the grave accent (l’accent grave)

- ë/ï/ü – the trema (l’accent tréma)

These accent marks serve several different purposes in the language. Sometimes they affect pronunciation, sometimes they don’t. Sometimes they can completely change the meaning of a word.

So how do you read, write, or pronounce these letters? What do the accent marks mean? And how can you remember all of the French accent marks, rules, and pronunciation? Let me walk you through them.

(By the way, if you’re still struggling with the French alphabet, we have a handy video for you!)

The Cedilla (La Cédille) Accent Mark in French

The cedilla accent mark in French looks like a little squiggle beneath the letter “c”: “ç”. This accent mark only goes with the letter “c” – it’s not found under any other letter.

It’s a simple symbol to understand: a ç (c with a cedilla) is pronounced like an “s”.

You’ll only ever see a “ç” before an “a”, “o”, or “u”. (Remember that “c” before an “e” or “i” is pronounced like an “s” anyway, so adding a cedilla wouldn’t change anything.)

Two common words that contain cedillas are garçon (“boy”, or “waiter” in a restaurant) and français (French!). You can also occasionally see it in English in loanwords like façade.

The Acute (L’Accent Aigu) Accent Mark in French

The acute accent mark in French is only ever found above an “e”, as in “é”. Its role is to change the pronunciation of the vowel.

An unaccented “e” can be pronounced several different ways, but when you see “é”, there’s no ambiguity. An é (e with an acute accent) is always pronounced the same way.

So what way is that? Many books and websites will tell you that “é” is pronounced like the English “ay”, as in “say” or “way”.

There’s just one problem with this piece of advice: it’s wrong. Sure, the “ay” sound is close to the French “é” sound, but it’s not quite the same. If you pronounce “é” like an “ay”, it will be a dead giveaway that your native language is English.

To understand how “é” is pronounced, let’s examine the English “ay” sound a little closer.

Try saying “say” or “way” very slowly, drawing out the vowel at the end. Notice that as you say “aaaaaay”, your tongue moves.This is because “ay” is secretly not one but two vowels said in quick succession. (Linguists call such double vowels “diphthongs”.)

The French “é” is the first of the two vowel sounds that make up the English “ay” diphthong. To pronounce “é” accurately, position your tongue like you’re about to say “ay”, but once you start making noise, don’t move your tongue or lips. Keep them steady for the entire duration of the sound.

As native English speakers, we often find it hard to shake the habit of “doubling up” this sound and pronouncing it like an “ay” – but with practice, you should remember.

(If you’re familiar with the International Phonetic Alphabet, note that the IPA for the “é” sound is /e/. Also note that the French “é” sound is the same as the Spanish “e” sound, which I explained in detail in point #2 of this article. Even if you don’t speak Spanish, you may find that explanation helpful for your French).

Also, if you want some tips on how to avoid sounding like an obvious foreigner, Benny has some advice for you in one of our podcasts!

The Grave (L’Accent Grave) Accent Mark in French

The grave accent mark in French can be found above an “a”, an “e”, or a “u” (à/è/ù). It does a few different things.

Firstly, it’s used above an “a” or “u” to distinguish words which have the same pronunciation but different meanings:

a vs à:

- a is the third-person singular form of avoir (“to have”)

- à is a preposition that can mean “at”, “to”, or “in”

ça vs çà

- ça is a pronoun meaning “it” or “that”

- çà is an interjection that’s hard to translate. It can express worry or surprise (like saying “uh-oh!”) or it can be mere verbal filler, like saying “hey” or “well”.

la vs là

- la is the feminine form of the word “the” – or in other contexts it can mean “her”.

- là means “there” or “that

ou vs où:

- ou means “or”

- où means “where”. Note that this is the only word in the entire French language where you’ll find a grave accent above the letter “u”!

You can also find a grave accent in déjà (“already”) and deçà (“closer than”), although “déja” and “deça” without the accent aren’t words.

Above an “a” or a “u”, a grave accent doesn’t change the pronunciation. Above an “e”, however, it tells you that the vowel is pronounced “eh”, like the “e” in “get” (IPA /ɛ/).

There are many ways to pronounce an unaccented “e” in French. The grave accent makes it clear that you must say /ɛ/, when otherwise the “e” might be a different sound, or silent.

The Circumflex (L’Accent Circonflexe) Accent Mark in French

The circumflex, which looks like a little pointy hat, can be found as an accent mark above all five vowels in French: â, ê, î, ô, or û. I’ll spend more time on the rules of this accent mark, since its usage is somewhat complicated.

First, it tells you how to pronounce “a”, “e”, and “o”:

- “â” is pronounced roughly like an English “ah” as in an American “hot” or British “bath”.

- “ê” is pronounced like an English “eh” as in “get” – the same as if it was “è” with a grave accent.

- “ô” is pronounced roughly like an English “oh” as in “boat” or “close”. It’s the same sound found in the French word au.

When placed over an “i” or “u”, a circumflex doesn’t change the pronunciation, except in the combination “eû”. Jeûne (“fast” as in a dietary fast) is pronounced differently from jeune (“young”).

So why bother writing a circumflex when it doesn’t affect pronunciation? The answer takes us back hundreds of years.

Take the word forêt, which means “forest”. As you might guess, the English and French words share a common root. As time went on, French people stopped pronouncing the “s”, but they continued to write it – it was a silent letter, of which English has many.

Eventually, it was decided to change the spelling of the word to remove the superfluous “s”. But for whatever reason, the French intelligentsia didn’t want to erase all trace that this “s” had ever existed – so it was decided to add a circumflex to the “e” in its place. The circumflex is an etymological tombstone – it tells you “hey, there used to be an extra letter here!”

Compare these French words to their English cognates:

- ancêtre – “ancestor”

- août – “August”

- côte – “coast”

- forêt – “forest”

- hôtel – “hostel”

- hôpital – “hospital”

- pâté – “paste”

- rôtir – “to roast”

Most commonly, a circumflex denotes a missing “s”, but it’s sometimes used for other letters. For example, âge (age) and bâiller (to yawn) were once spelt aage and baailler.

The circumflex is also handy for distinguishing certain pairs of identically-pronounced words:

sur vs. sûr:

– sur is a preposition meaning “on”, or an adjective meaning “sour”.

– sûr means “sure” or “certain”. Note that the circumflex is still present in inflected forms like the feminine sûre, or in derived words like sûreté (security).

du vs. dû:

– du means “of the” – it's a contraction of de (of) and le (masculine form of “the”).

– dû is the past participle of devoir – “to have to”. Unlike sûr, the circumflex is not kept in the inflected forms: so it's dû in the masculine singular but due, dus, and dues in the other three forms.

mur vs. mûr:

– un mur is “a wall”.

– mûr means “ripe” or “mature”, as well as being a slang term for “drunk”. The circumflex is preserved in the inflected forms (mûre, mûrs, mûres), and in related words like mûrir (to ripen.)

This might sound like a lot, but a little practice each day will help! We interviewed Will, a fellow French learner, about his language journey and advice in our podcast:

The Trema (L’Accent Tréma) in French

Finally, we have the French trema accent mark: two little dots above a letter. It can be found above an “e”, “i”, or “u”: ë, ï, ü.

The trema is also sometimes called a “diaeresis” or “umlaut”, although technically it’s not an umlaut. The umlaut and diaeresis are unrelated things that evolved in different places and only look the same by coincidence – but that doesn’t matter here.

You may recognise the trema from the names Zoë and Chloë. Here, the trema tells you that the “o” and “e” are pronounced separately – so they rhyme with “snowy”, not “toe”.

(If only David Jones had taken the stage name “Boë” instead of “Bowie”, all the confusion about its pronunciation could have been avoided).

Some English style guides suggest you use the trema (also known as a “diaeresis”, pronounced “die-heiresses”) for a host of other words, like reëlect or coöperate. However, in practice almost no-one does this.

In French, the trema works the same way, and it’s much more common than in English. It’s written over the second of two vowels to tell you that they must be pronounced separately, whereas without the accent they might combine into a completely different sound:

- coïncidence (coincidence)

- Jamaïque (Jamaica)

- Noël (Christmas)

This is by far the most common use of the trema.

There a confusing exception when you consider adjectives which end in a “gu” – like our friend aigu (acute), as in l’accent aigu.

Why we want to use aigu with a feminine noun, like douleur (pain)? Normally we’d add a silent “e”. The problem is that “gue” in French is pronounced as “g”, with a silent “e” and “u” (You can see the same rule in English words like “fugue” or “vague”).

To get around this problem, French uses a trema: the feminine form of aigu is aigüe, as in douleur aigüe. Since the French Spelling Reform of 1990, the trema is officially supposed to go on the “u”, although you’ll often still see people writing aiguë.

So now we’ve wrapped up what each French accent mark does, and next we’ll talk about how to type them on a PC and Mac. But first, I can’t help but mention this video Benny did about how to overcome some French challenges–including writing and speaking. Check it out!

How to Type French Accents

I’m sure you’ll want to know how to type French accent marks. French computers generally use the AZERTY keyboard layout, which has some major differences from our familiar QWERTY – including some special keys for typing accents.

Learn to type in a new layout if you’re feeling hardcore. For everyone else, there are fairly convenient ways to type accents in French (or any other language) on QWERTY. Here’s how you can do it on a PC or a Mac:

How to Type French Accents On a PC

The following shortcuts should work to type French accent marks on a PC keyboard:

- To type “ç” or “Ç”, press Ctrl + ,, then “c” or “C”.

- To type “é” or “E”, press Ctrl + ’, then “e” or “E”.

- To type a vowel with a circumflex press Ctrl + Shift + ^, then the vowel.

- To type a vowel with a grave accent press Ctrl + `, then the vowel.

- To type a vowel with a trema press Ctrl + `, then the vowel.

If that doesn’t work, you can try inputting the character code directly.

Each accented character can be entered with a four-digit code. Simply press the “alt” key, then enter the French accent codes below. (Note: you’ll need to enter them with the number pad on the right-hand side of your keyboard, not the number keys above the letters.)

| Character | Code Lowercase | Code Uppercase |

|---|---|---|

| ç | Alt + 0199 | Alt + 0231 |

| é | Alt + 0233 | Alt + 0201 |

| â | Alt + 0226 | Alt + 0194 |

| ê | Alt + 0234 | Alt + 0202 |

| î | Alt + 0238 | Alt + 0206 |

| ô | Alt + 0244 | Alt + 0212 |

| û | Alt + 0251 | Alt + 0219 |

| à | Alt + 0224 | Alt + 0192 |

| è | Alt + 0232 | Alt + 0200 |

| ì | Alt + 0236 | Alt + 0204 |

| ò | Alt + 0242 | Alt + 0210 |

| ù | Alt + 0249 | Alt + 0217 |

| ë | Alt + 0235 | Alt + 0203 |

| ï | Alt + 0239 | Alt + 0207 |

| ü | Alt + 0252 | Alt + 0220 |

How to Type French Accents On a Mac

Generally, you can type French accent marks on a Mac as “special characters” by using the Option/Alt key. That’s the one labelled “⌥”, between “ctrl” and “cmd”. Here’s what you need to know for French:

| Character | Keys |

|---|---|

| cedilla | Alt + c |

| acute accent | Alt + e |

| circumflex | Alt + n |

| grave accent | Alt + ` |

| trema | Alt + u |

To add a letter with a diacritic, press the appropriate key combination, then press the key for the letter you want the diacritic to belong to. For example, to type “ì”, press “alt” + “`” together, then release them and press “i”.

The exception is the cedilla – pressing “alt” + “c” inputs a “ç” directly, without the need to press “c” again afterwards.

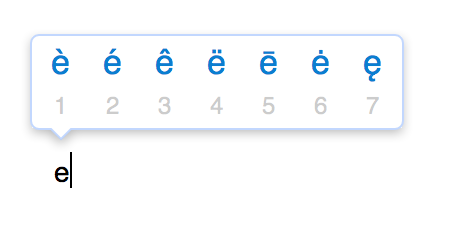

Depending on your keyboard and system settings, you may also be able to type special characters by holding down a regular letter key. For example, when I hold down “e” on my Mac for a second or so:

Now to get the accented “é”, I just press “2”.

Knowing French will make a trip to the beautiful south of France even more spectacular!

French Accent Marks – Have Your Say

That covers it! As you can see, the rules for accents in French are a bit complicated, but they’re not impossible. Remember that they don’t always affect pronunciation: so if your focus is speaking, not every accent rule needs to be studied in great detail just yet.

And if you’re interested in continuing, I highly recommend FrenchPod101 and Story Learning French. They make learning French fun and easy and will give you plenty of opportunities to practice your accent marks!

Social